If you are reading this blog you probably already know that health testing is important before deciding whether to breed a dog. Of course; we want to produce healthy puppies. But did you know that some health testing is intended so that we can breed dogs who are carriers of – and in some cases even affected by – various hereditary diseases?

Yes, you read that correctly. Some dogs with disease genes *should* still be bred, as long as doing so doesn’t hurt the dog and we can be reasonably sure that no puppies produced will suffer. And of course the dog should meet other breeding criteria such as being structurally sound, having a good temperament, and generally being a proper representation of their breed (or otherwise representing what the breeder is intending to produce).

Why? Because genetic diversity is critical for the health and future of each breed, and if you spay/neuter every dog with imperfect health you will soon lose that diversity. Here’s an article on this topic from Paw Print Genetics: Breeding Carriers of Canine Recessive Diseases- Why It Should be Considered

Genetic Diversity is a Top Health Factor

Genetic diversity, especially at genes important for immune functioning within the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), has been associated with fitness-related traits, including disease resistance, in many species.

— Does Genetic Diversity Predict Health in Humans? – PubMed Central

Breeding with an ever-reducing genetic population means that inbreeding becomes more common, resulting in the opposite of genetic diversity – inbreeding depression. Continued generations of lowered diversity will suffer the repercussions of being more and more inbred, such as:

- a weakened immune system/lower disease resistance

- more cancers at earlier ages

- reduced fertility

- more genetically untestable health conditions including epilepsy, bloat, autoimmune thyroiditis, and Addison’s disease

Here is a detailed study specifically on the effects of the mid-century genetic bottleneck accidentally created in Standard Poodles while breeding for top winning show dogs starting around the 1950’s. The paper discusses how large-scale inbreeding and loss of diversity has come to result in some diseases we now consider to be ‘fixed’ within the breed (genes likely carried by essentially the entire breed, and therefore can’t develop a test for). The specific diseases researched were Addison’s Disease and Sebaceous Adenitis: The effect of genetic bottlenecks and inbreeding on the incidence of two major autoimmune diseases in standard poodles, sebaceous adenitis and Addison’s disease.

Important Terminology

| Autosomal | Traits controlled by one gene, located on a numbered chromosome (not on the sex-linked X or Y chromosomes) |

| Polygenic | Traits that are controlled by multiple genes |

| Recessive | Two copies of the gene (one from each parent) are needed to produce the disease |

| Dominant | One copy of the gene is needed to produce the disease |

| Incomplete Penetrance | Not all dogs with the gene will develop the condition, or could have it to a lesser extent than a dog with two copies |

| Hybrid Vigor (Heterosis) | The tendency of a cross between separate species (or distinct breeds in the case of dogs and some other organisms) to be improved over both parents in some way/s (e.g., better health, faster growth, higher fertility). Note – males of cross-bred species tend to be infertile, such as mules, ligers, bull crosses, various plants, etc. |

| Epigenetic | Refers to environmental and behavioral factors which affect how the body ‘reads’ the DNA, and can be passed to future generations; example factors include diet, stress, pollutants, exercise types, age, etc. |

| Preservation / Conservation Breeder | A breeder whose strategy includes looking at the big picture of maintaining and improving the history and current state of their breed, as well as planning for the long-term genetic health of the breed into the future. |

| Mainstream | Refers to the genetic families that are common within the breed; not individual genetic traits, but relationships towards each other (genetically cousins, half-sibs, etc even if the written pedigree seems unrelated). |

| Outlier | Refers to dogs who have a significant number of uncommon/rare genes which make them less genetically related to the mainstream population. These are the dogs who can help bring more genetic diversity into the breed’s overall population. |

| Inter-variety | In Poodles, refers to matings between parents of the different size varieties (generally Standard to Mini or Mini to Toy). |

Phenotypic Testing

Phenotype refers to the physical characteristics which can be seen and measured in any given dog, resulting from a combination of genetic and environmental influences. In relation to health testing, these are traits for which we don’t yet (and may never) have recognized genes to test.

In most cases we consider phenotype health issues to be polygenic (being controlled by multiple genes), and often also multifactorial (being effected by multiple factors including genetics, epigenetics, and environmental influences such as weight, diet, other diseases, injuries, living environment, etc). These are the tests that tell us the most about the actual health – on that day – of the dog in front of us, but they don’t give us a solid answer to whether a dog might produce a pup with any of these traits, or even if they will develop it themselves in the future. Phenotype testing includes things like x-rays of various joints, specialized eye exams, heart auscultation and echocardiogram, blood testing for current indications of poor thyroid or adrenal function, etc.

These are the veterinary tests that are performed hands-on, some requiring a specialist to perform the exam. Many of the tests require specialized equipment (x-ray machine, various types of ultrasound equipment, ophthalmology tools) and some procedures need sedation.

Some tests – like patella and cardiac exams – can be done officially any time after 12 months, while others like hip and elbow certifications aren’t official unless performed after 24 months. Testing such as eye exams are recommended to be repeated every 1-2 years at least through-out the dog’s breeding career, and other tests are recommended to be repeated at least a couple of times through maturity. The primary health testing and recording database in the US is the OFA (Orthopedic Foundation for Animals), and most reputable breeders will pay to have their dogs’ results published on their website for anyone to find and verify. The tests can all be performed and assessed independently of OFA, but generally there will be no verification available in those situations. Penn-HIP is another hip assessment program, basing their findings on different factors than the OFA assessment – some breeders opt to have both exams done to get the most feedback available.

OFA grants a CHIC (Canine Health Information Center) number to dogs who have received and published on OFA the minimum health testing recommended by their breed’s parent club (regardless of whether they pass/fail; the CHIC is about knowing the results and sharing them publicly). In Standard Poodles, only 3 tests are needed – hip x-rays, a single eye exam, and an elective of either a basic/advanced heart exam, thyroid blood test, or sebaceous adenitis biopsy. There are many other tests that a breeder may choose to perform for a more thorough picture of the dog’s health and soundness – for example, elbows, patellas and other joints can be assessed, an echocardiogram of the heart, verification of full dentition, etc. Some breeds have additional testing for hearing issues, breathing issues, long-term heart monitoring, and more.

The cost of phenotypic tests is significant; $700-2,000 is a safe estimate for most dogs to get the recommended tests for their breed. Many breeders will also need to book months in advance and travel to get to a vet who is qualified and skilled at performing these tests – most of these are not ones that can/should be performed by a general practice vet.

Genetic Testing

Genotype refers to the DNA and what genes actually exist in a dog, and therefore can or can’t be passed on to offspring.

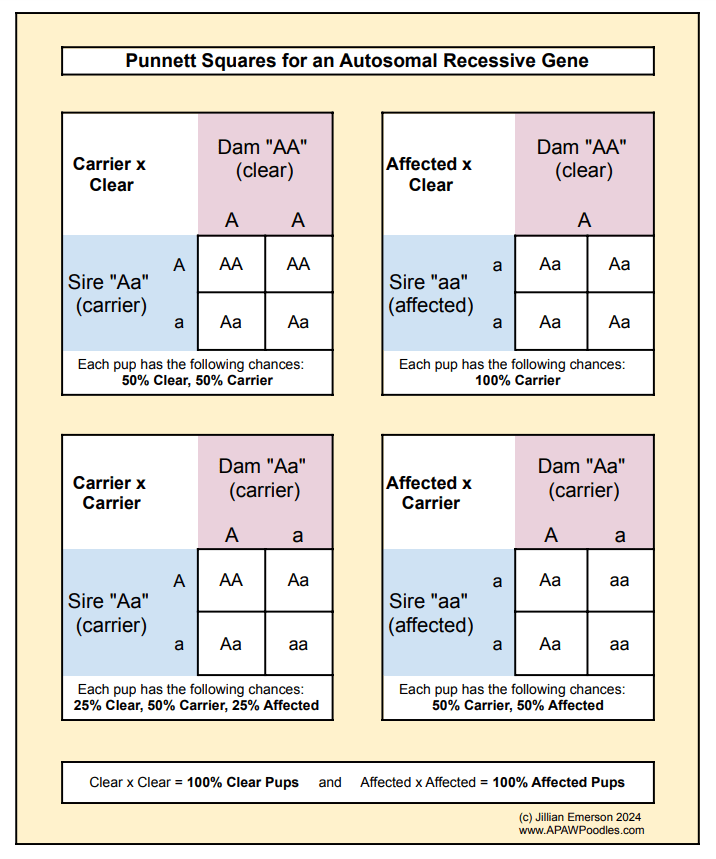

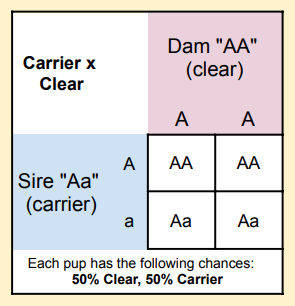

Genetic tests don’t tell you if a dog should or shouldn’t be bred, but they do tell you if a certain mate is a safe pairing for that dog or not (in relation to the specific diseases tested). Most of the genetic tests that have been developed are for traits which have an inheritance pattern called autosomal recessive. This means that in order for a pup to inherit the disease they would need to receive the mutated copy of the gene from both parents. As long as at least one parent won’t pass on the same disease gene, no pup will be affected and therefore the mating of a carrier is acceptable. Some puppies will be carriers (having received one copy of the mutated gene), but in most genetic diseases this does not put them at risk for developing the condition.

If a dog has two copies of a disease gene (genetically affected, though may or may not show physical symptoms), it can sometimes still be worth breeding them if they are a fantastic dog and/or have important genetic diversity not available to the breed from a healthier relative. Why is this considered acceptable practice? Because the dog can still only pass a single copy of the disease to each pup – every pup will carry it, but if the mate is clear then no pup will be affected. The best pups – those who inherited the diversity and other desirable characteristics – can then be bred to clear mates and the resulting pups will either have one or no copies of the disease. In this way the diversity can be saved without producing any affected puppies, and in just a couple of generations the disease gene can be removed from the line.

A Punnett Square is the best way to demonstrate how simple autosomal recessive inheritance works.

There are some genetic diseases which have different modes of inheritance whereby a single copy can still produce affected puppies – vWD (von Willebrand’s Disease) is a common example of this; as an autosomal dominant gene with incomplete penetrance, a single copy of the gene can still result in a dog who develops the disease but to a milder degree than if they had inherited two copies. CDDY (Chondrodystrophy) and it’s consideration as a ‘risk factor’ towards the potential development of IVDD (Intervertebral Disc Disease) is another example; many breeds have this gene spread heavily throughout the population, with a much smaller percentage of the population actually developing any related health trouble. Research by the UC Davis Vet Genetics Lab indicate that 57-61%+ of Toy and Miniature Poodles have 1 or 2 copies of the CDDY gene yet a far fewer percentage of small Poodles are ever affected by IVDD so the presence of the gene is somewhat considered “normal”, though with desire to breed away from when possible. The gene has not been found in many Standards and most are never tested because we don’t see much IVDD in the variety, but it becomes an important factor to consider for breeders who have lines that combine the size varieties – what if the gene has more impact on dogs of a larger size?

Many of the diseases we don’t yet have tests for are likely polygenic, meaning that there are probably a combination of genes that are involved in the expression of the disease. These diseases with other inheritance patterns are a bigger challenge to breeders and each trait needs to be looked at individually to weigh the specific risks and benefits of a mating.

Genetic testing is available for hundreds of different diseases found across the canine species, but generally only a handful of tests apply to each breed… there are around 8 genetic tests applicable to Standard Poodles and a few more applicable to Minis and Toys which need to be considered by breeders who include any inter-variety breeding practices. The most widely known genetically testable diseases in Poodles are von Willebrand’s Disease, Neonatal Encephalopathy, Degenerative Myelopathy, Chondrodystrophy and a couple variants of Progressive Retinal Atrophy.

In addition to disease genes, genetic testing can also be done to determine traits like what coat colors a dog carries, and in other breeds/mixes shows the coat types carried and other potential details a breeder may be interested in.

Since a dog is born with their DNA already set, genetic testing can be accurately done at any age when the sample can be taken (recommended around 2 weeks or older for saliva samples, and a bit older for blood samples). There are many labs to pick from for sending DNA samples for testing, and the range for typical Poodle tests is around $170-400, with some tests only being available at specific location/s. DNA test results from most companies can be submitted to OFA to be added to their database (again, for a fee), though many breeders just share the results on their own website or privately on request.

Assessing Genetic Diversity

Before DNA testing became popular in the last couple of decades, breeders used pedigree-based Coefficient of Inbreeding (COI) percentages to assess a dog’s direct lineage and determine how inbred they were. All purebreds are inherently inbred to some degree because that’s how breeds are formed and characteristics are set with predictability. A pedigree is needed for assessment, and it needs to go back a significant number of generations – ideally back to the founders of the breed (who would not be related to each other); realistically, most COIs are calculated on 5-10 generations and often with large missing sections, making them low estimates. A COI essentially calculates how likely a dog is to inherit an identical gene from each parent. The calculation considers that each parent gives 50% of their genes to each offspring, which assumes 25% of shared genes with each grandparent, 12.5% shared with each great-grandparent, 6.25% with great-great-grandparents, etc. This starts off well, but you can quickly see that the calculation loses accuracy with every generation beyond the parents because there is no way to know which percent from each grandparent were passed down! BetterBred has an excellent article on this topic, with graphs to illustrate: COI is Useless.

Here is a sample COI calculator from LabGenVet.

Here is a detailed article regarding inbreeding and types of COI assessment from Embark, which uses a genetic COI based on the full canine genome (across the species, not separated by breed).

So, how to assess actual genetic diversity in a dog, and apply it to a breeding program? The Canine Genetic Diversity test by UC Davis provides critical data analyzed from a simple saliva sample, and the algorithms of BetterBred let us evaluate how the dog compares to others within their breed, including assessing close relations (who may not share many/any relatives within many generations!) as well as looking at potential mates to assess genetic compatibility – thereby allowing us to maintain and increase genetic diversity averages for the future pups.

I am personally a huge fan of BetterBred and UC Davis’ diversity test – I have tested well over 60 dogs including many whole litters, and have used the results to guide my breeding decisions and help pick my keeper pups since the testing and BetterBred became available in 2016. The information I can learn about my dogs is fascinating, and knowing so many tested relatives has added to the depth of information the results give me.

Hybrid Vigor

Genetic diversity is also where part of the notion of “hybrid vigor” comes up in regard to dogs of mixed breed status – if the parent breeds don’t have the same genetic diseases, then the pups won’t inherit multiple copies of the same genes… But the pups could be carriers (inherit 1 copy) of many diseases, and when bred in the next generation could produce any of the parent breeds’ diseases if genetic testing isn’t used to avoid it. The overall vigor of a statistically stronger immune system is valid, and is a general result of genetic diversity, which mixed breed dogs certainly have! Purebreds who have been cautiously bred to keep and cultivate genetic diversity tend to see similar increased vigor over purebreds who have been tightly line-bred or inbred especially in the extremes of show culture breeding repeatedly to families of top winners, and puppy mills breeding repeatedly to relatives because it’s cheapest and most convenient.

Outcrossing

‘Purebreds’ by default have a gene pool reduction as generations pass, and preservation (or conservation) breeders include genetic diversity as a critical component of their breeding programs to keep diversity available in their breed. It is important to breed diverse dogs (outliers) into the mainstream (breed-typical genetic lines) of the breed to help the health of immediate upcoming generations, but it is also critical to keep diverse lines which remain undiluted for the opportunity to outcross further generations into the future. Plenty of breeds seem to have already lost the ability to outcross to a distinct line; they have significant health issues that exist in every known pedigree and therefore can’t be bred away from. Some of these breeds have turned to careful outcrossing to a similar breed that does not share those health issues, and carefully maintaining this influx of genetic diversity while breeding back to their original breed. Some of these outcross projects are sanctioned by kennel or breed clubs to save their breeds from extinction, while other outcross projects are undertaken by concerned breeders who don’t want to waste their little remaining diversity waiting for official club approval. Some breeds with outcrossing projects include Bernese Mountain Dogs (BMD Vitality Project), Chinook (Chinook Breed Conservation Program), Doberman Pinschers (Doberman Preservation Project) – and one of the original outcross projects was for Dalmatians (LUA Dalmatian Backcross Project).

Inter-Variety

We are very lucky in Poodles to have our 3+ size varieties (Toy, Miniature, Standard in the US) which can be bred together without needing to bring in a different breed. These inter-variety genetic outcrosses are recognized as acceptable by many of our breed registries around the world including the AKC and CanKC; unfortunately UKC considers Standards to be a separate breed from Minis and Toys. The Standard to Mini combination generally results in high diversity pups in a smaller size than average Standards, and often with a bit more spunk or drive which the Mini variety tends to be known for. The offspring can then be bred back into the Standard population to return to producing consistently larger dogs, or some breeders prefer to also select for a smaller size range and/or other characteristics of the Mini line they chose to breed into – temperament or physical traits.

“Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water!”

In dog breeding this phrase is often used when an overall wonderful dog has a small set of undesirable characteristics, especially if they are one of a small number of breedable dogs with their specific diversity. They may still be worthy of being carefully bred to a mate that improves on those traits so that the line (and diversity) can be saved and improved upon rather than being lost permanently.

Health Guarantees

Ultimately there are no guarantees that any dog will remain healthy to their senior years. A dog is a living, breathing being. No matter how much care and consideration is put into generations of breeding decisions, anything can happen. There are the obvious accidents like getting hit by a car or lost in the woods, but there are countless other factors that can lead to injury and/or death – diet, exercise, medication, environmental treatments… all can lead to improved health and safety as well as directly contributing to a cause of death. Breeders work diligently to stack the odds as favorably as possible, but ultimately the only guarantee we can make is that of the million possible health conditions that exist, the pup we sold doesn’t carry the genes for the small handful we could genetically test their parents for. The best any breeder can do is warranty what they will offer if a pup from them does get sick, though even that has a lot of caveats now that we know how many illnesses are caused/influenced by environmental factors that are completely out of the breeder’s control once the pup goes home.

Many breeders are willing to share their contract with potential homes, letting you know up front what their warranties are and what factors might void them.

When selecting a breeder for your next canine companion or working partner, ask lots of questions about how a breeder runs their program and assesses their breeding stock. Don’t be shy to ask a breeder to explain what, how or why behind their decisions – their answers will really help you understand their knowledge and reasoning on the subject, and will help you decide if they are the right breeder for you.

Check out more blog posts below – I promise, most are much shorter than this one!

Leave a comment